When you think of green alcohol, absinthe is likely the first product that comes to mind. Given its controversial history, that’s not a surprise. But another green alcohol has been on the market for more than 400 years, steadily rising to fame because of the secrecy of its recipe and its vegetal, spicy flavor: chartreuse. With 130 herbs, spices, barks, and roots in every batch — and a recipe known to only two people at any one time — there’s no other liqueur quite like it.

An Alluring Alcohol

The subtle mystique of Chartreuse is surprisingly widespread. The drink has appeared in history, literature, and film over the centuries. It’s said that Welsh journalist and explorer Sir Henry Morton Stanley carried the liqueur through Africa on his search for Dr. David Livingstone; that French general and eventual president Charles de Gaulle enjoyed Chartreuse-spiked hot chocolate; that actor Bill Murray has appeared at parties and bought shots of Chartreuse for everyone. In The Great Gatsby, Jay and Nick talk over glasses filled with the liqueur. In the novel Sweet Thursday, the characters drink martinis made with Chartreuse. The unique alcohol has even merited mention in films by Alfred Hitchcock and Quentin Tarantino.

Chartreuse’s trademark vibrant-green hue comes from the chlorophyll in its botanical ingredients. Its natural ingredients are put through multiple macerations before the concoction is aged. And while Green Chartreuse, the original liqueur, has gained much more recognition than its cousin, Yellow Chartreuse is thought to be made with similar herbs in different amounts and perhaps macerated for a different length of time, resulting in a naturally pale-gold coloring. The green-yellow hues of these liqueurs are so unique that the color we call “chartreuse” is actually derived from the drink itself.

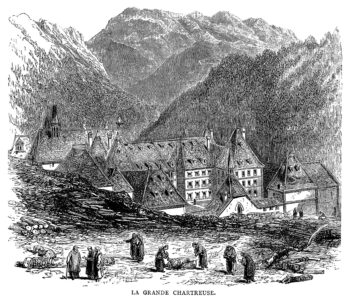

Despite the complexity and precision of the Chartreuse recipe, only two people in the world know the 130 herbal ingredients. The distillers are monks of the cloistered Chartreuse Order, or Carthusians, who take a vow of silence and live in solitude and simplicity. A monk’s hermitage is his retreat. The Carthusian monastery is nestled in the Chartreuse Mountains of St. Pierre-de-Chartreuse, France, with a sign posted outside asking for silence. Cars and buses must stop at a certain distance to avoid disturbing the monks’ peace and solitude. And when one film director, Philip Gröning, wanted to make a documentary about the Carthusians and their day-to-day lives, it took 16 years to negotiate an agreement. It should come as no surprise that they carefully keep the formula for Chartreuse to themselves. What is surprising are the lengths to which monks have gone to keep the secret recipe tightly in their grasp.

Muddling Through History

The history of Chartreuse may not be as well known as that of absinthe, but it’s no less fraught with contention. In 1605, the Carthusian monks in Vauvert, France, were gifted an ancient manuscript from François-Annibal d’Estrées, who was an army officer for King Henry IV. While the author of the manuscript remains unknown, it’s thought to have been a 16th-century alchemist, who nicknamed the recipe “Elixir of Long Life.” The manuscript was so complex that it wasn’t unraveled until the beginning of the 18th century, when it was sent to the monastery La Grande Chartreuse in the mountains of France. There, in 1737, an apothecary named Frère Jerome Maubec finally deciphered the text and wrote out a practical formula to create the elixir. That creation is still sold today, and it’s called “Elixir Vegetal de la Grande-Chartreuse” (69 percent alcohol, 138-proof).

This all-natural preparation of botanicals suspended in wine alcohol was so tasty that those who could get their hands on it often drank it as a beverage rather than a tonic. And so, in 1764, the Carthusian monks adapted the recipe into a milder liqueur now known as “Green Chartreuse” (55 percent alcohol, 110-proof). Its success was immediate.

Twenty-five years later, the French Revolution began, and all religious orders were displaced from the country. When the Carthusian monks left in 1793, one copy of the manuscript remained at the monastery. The monk who carried the original was arrested soon after leaving La Grande Chartreuse, but he was able to smuggle the manuscript to a friend, who, sure that the monks would never return to France, sold the manuscript to pharmacist Monsieur Liotard. Liotard never produced the elixir himself, and his heirs later gave the manuscript back to the Carthusians, who returned to their monastery in 1816, resuming production. In 1838, they developed a sweeter and even milder form of the liqueur, Yellow Chartreuse (40 percent alcohol, 80-proof). They built a distillery in 1860 at Fourvoirie, France, not far from the liqueurs’ namesake monastery.

Forty years of quiet production flowed until 1903, when the French government nationalized the Chartreuse distillery. The monks were once again expelled. While the Carthusians built new distilleries in Tarragona, Spain — the liqueur from which was nicknamed Une Tarragone — and Marseille, France, the French government sold the Chartreuse trademark to a group who set up the Compagnie Fermière de la Grande Chartreuse. This group did, for a time, sell their version of Chartreuse, but they went bankrupt in 1929. Friends of the monks acted quickly; they purchased the shares of the failed company and offered them to the Carthusian monks, who once again regained their trademark and returned to their distillery — for a time. The distillery at Fourvoirie was destroyed in a landslide in 1935, and the monks moved production to Voiron, France, where it remains to this day.

Modern Mixology

Today, the Carthusian monks select, dry, crush, and mix their ingredients within the monastery, in their former bakery space. They keep the mixtures in carefully sealed and numbered bags before transporting them to distilleries in Voiron, and, more recently, to Aiguenoire, France, a second location officially inaugurated in 2018. The botanicals are left to macerate in alcohol before being poured into stills to begin the distillation process. The distillate initially comes out clear, but undergoes multiple additional botanical macerations that ultimately create the characteristic chartreuse color. The liqueur is next aged for years in oak casks in the distillery at Voiron, home to what is purportedly the world’s longest liqueur cellar– though the monks are as secretive about its dimensions as about the ingredients of the liqueur within.

A company called Chartreuse Diffusion has been in charge of bottling the products from the monastery since 1970, as well as packaging, advertising, and selling the liqueur. Bottling takes place on the ground floor of the Voiron distillery, directly above the cellar, although the monks have plans to relocate the bottling line to Aiguenoire in 2020. Wherever it takes place, the bottling is sure to continue to be as important to the finished product as the distillation process; one of Chartreuse’s most appealing qualities is the way it continues to age and improve in the bottle.

Since Yellow Chartreuse hit the market in 1838, other versions of the liqueur have emerged from the Carthusian monks. As it matures, a small portion of each batch of Chartreuse is selected to age for an extra length of time, and then packaged and marketed as Vieillissement Exceptionnellement Prolongé (V.E.P.). Between 1840 and 1880, and then again from 1886 to 1900, a White Chartreuse was in production. In 1984, Liqueur du 9° Centenaire was created to commemorate 900 years since the foundation of the Chartreuse Order. In 2005, to mark the 400-year anniversary of the gift of the original manuscript, a version named 1605 was developed. Finally, in 2007, the monks released Liqueur des Meilleurs Ouvriers de France, a golden-yellow liqueur they made in collaboration with the country’s master sommeliers.

A Spirited Secret

Over the years, avid admirers have tried to guess the Chartreuse recipe for themselves. At different times described as “intensely floral, “very sweet,” “mellow,” and “herbaceous,” none have come close to guessing all 130 ingredients — not to mention the undisclosed maceration and aging times. Still, in the early 1900s, John Tellman confidently claimed to know a handful of the herbs, which he published in his book The Practical Hotel Steward: “Chartreuse Green is made from cinnamon, mace, lemon balm, dried hyssop flower tops, peppermint, thyme, costmary, arnica flowers, génépi, and angelica roots.”

Did he get any of the ingredients right? The monks certainly aren’t telling. Though they once released a photograph of the original, 17th-century manuscript for promotional purposes, a measuring glass placed on top of the parchment hides many of the formula’s details. Just recently, a Carthusian monk answered one visitor, intrepid enough to ask about the ingredients in the base elixir, “Hamburger and goat cheese.” With the allure of secrecy drawing in eccentric and casual consumers alike, one thing is certain: The monks are willing to keep the Chartreuse recipe to themselves for another 400 years.

For More:

- Chartreuse Liqueur Cocktail Recipes: Get to know Chartreuse with these two recipes, which feature the green and yellow varieties of the fragrant liqueur.

- Homemade Liqueurs with Herbs: Herbs, spice and everything nice for after-dinner liqueurs and other alcoholic drinks.

Haley Casey is an editor at Fermentation, which gives her a chance to gather new ideas for healthy living and delicious recipes, as well as to read and write creative content. She greatly enjoyed her first taste of Chartreuse this past spring.