Photo by Shutterstock/netsign33

Maureen O’Prey isn’t your typical historian; the redheaded Baltimorean is just as likely to be found at the bar as she is in the archives — all in the name of research, of course. And that’s lucky for the rest of us. With the help of her partner-in-crime, Judy Neff, O’Prey marries her passions for beer and history to bring ancient brews hopping back to life.

For O’Prey, the true lure of history lies in connecting to the people who forged the way. And when it comes to Baltimore, Maryland, a beer town that was home to more than 40 breweries at its peak in the late 19th century, there’s no shortage of colorful characters to toast.

Baltimore’s Brewing Past

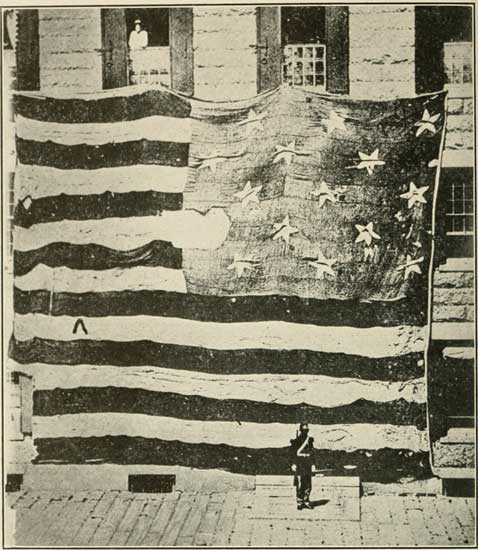

There’s no doubt that beer is a touchstone of Baltimore’s character — just look to the omnipresent Natty Boh sign that winks over the skyline. The fermented beverage has been around since Baltimore’s beginnings, so much so that Mary Pickersgill even sewed the stars upon Fort McHenry’s Star-Spangled Banner on the floor of a local brewery. As a major seaport populated by German and Eastern European immigrants, the city’s beer economy flourished from Colonial times until Prohibition.

The original flag sewn by Mary Pickersgill that flew over Baltimore during the War of 1812. Photo by Wikimedia/George Henry Preble

Ironically, however, it was an overseas adventure that sparked O’Prey’s interest in her hometown’s brewing history. After visiting the Guinness Storehouse in Dublin, Ireland, she realized how little she knew about the roots of beer brewing in her own backyard.

This sent O’Prey down a rabbit hole of research, and she ended up uncovering enough historical gems to fill her two books, Brewing in Baltimore and Beer in Maryland: A History of Breweries Since Colonial Times. Over the span of her decade-long research saga, she was struck time and time again by the dominant yet overlooked role that women played in early brewing culture in Baltimore and beyond.

“Before industrialization, beer-making was the purview of women. The females took care of the family, the kitchen, and the hearth, and brewing was always included in that,” O’Prey says. “During early American colonization, you had to be self-sufficient to survive. If you left for the Colonies without a wife that could brew, you had to get your beer somewhere else.”

The colonists consumed copious amounts of low-alcohol beer, but they weren’t being lush — they were being practical. In the days before appropriate sewage treatment, drinking unboiled water could be a death sentence. Alcohol-based drinks were less likely to spread disease than water, and had a longer shelf life than nonalcoholic beverages. The beverage was so important that soldiers were even wooed into war by the promise of a free daily quart of spruce beer.

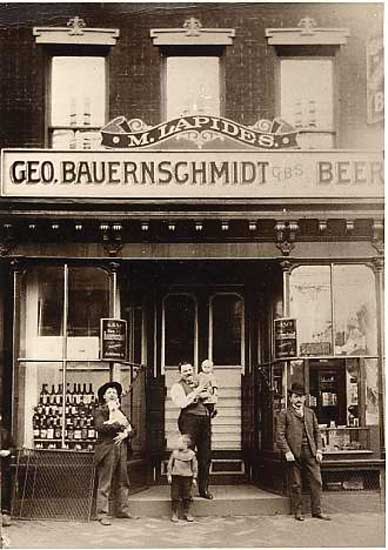

Photo by Flickr/The Jewish Museum of Maryland

When colonization increased in Maryland, taverns began popping up, and they soon became the social centers of their towns.

“It was the mail stop, gossip spot, and literal early courtroom. And, just like in the home, women were making the beer in taverns,” O’Prey says.

For married women, the tavern deed would be in their husband’s name, but the magistrates knew who was ultimately running it all. And when America stopped receiving imports from England, it was the women who went out to find hops and barley to keep the supply going.

When new technology and greater profits entered the picture, the brewing baton was transferred to men. It wasn’t until the modern era that women came back to brewing. For O’Prey, one of the most exciting things about the current craft beer renaissance is touching that piece of the past again, as more and more women seize back the baton.

The Bauernschmidt Brothers

One such trailblazer is Judy Neff, the brewer and owner of Baltimore-based Checkerspot — and the mad scientist to O’Prey’s history buff. The two met during the research stages of O’Prey’s first book and immediately bonded over their mutual love of craft beer.

Neff was bitten by the homebrewing bug in 2003, shortly after moving to Baltimore to pursue her doctorate in microbiology at Johns Hopkins University. In 2012, she joined forces with three fellow female brewers to launch Baltimore Beer Babes, an effort to invite more women into the craft beer world.

“Our goal was to see a woman amongst a group of guys telling them what they should drink for once,” she says. “In barely a decade, I’ve seen such a change; women are so much more informed. Baltimore Beer Babes is education, camaraderie, and of course, lots of fun.”

Judy Neff is the brewer and owner of Checkerspot, the Baltimore brewery behind re-creating the Bauernschmidts’ original recipe. Photo by Shawn Seidel

When Neff decided to open Checkerspot, she and O’Prey knew it was time to get to work re-creating historic recipes, just as they’d always discussed. Baltimore’s storied brewing past offered countless possibilities, but one particularly spirited tale struck both women as the perfect start to their collaboration: beer from hillbilly gold.

In this case, the hillbillies were actually one of Baltimore’s most prolific brewing families: the Bauernschmidts. Before immigrating to Baltimore, the three Bauernschmidt brothers grew up in Bavaria in conditions that were less than ideal. Young George, John T., and John J. were forced to sleep with the animals in their basement to stay warm.

“They had so many skills and talents, but mid-19th-century Germany wasn’t a place where they could’ve done better for themselves,” O’Prey says. “Even though they were surrounded by three prime hop brewing regions, they left their homeland in search of the American dream.”

Once the brothers arrived in Baltimore, they each opened their own brewery. George’s Greenwood Brewery, which he later renamed George Bauernschmidt’s Brewing Company, was the most successful of the bunch. Though it had modest beginnings as a small-capacity lager beer operation, it took off when he added a tavern, hotel, and, most importantly, an ice machine, which allowed him to cool the beer down before fermenting it in tanks.

“George was one of the earliest brewers to embrace the technology of the Industrial Revolution, and the result was the best beer in the region,” O’Prey explains. “This was the first time George made a profit; before, he was just breaking even.”

Photo by Checkerspot

By 1887, production exceeded 60,000 bottles, making his achievement of becoming the first brewery in Baltimore to bottle beer on its own premises all the more impressive. George Bauernschmidt’s Brewing Company became one of the first stock breweries in the region, with family members holding most of the stock. With this newfound wealth, the entire family moved into houses on the same city block off Gay Street and North Avenue.

The Bauernschmidts weren’t greedy with their money; O’Prey says they were philanthropists who funded countless causes in Baltimore, from orphanages to hospitals. This giving streak wasn’t limited to just their clan, either.

“On Gay Street, all the brewers went the extra mile for their community. Together, they’d clean the streets and take care of litter, and pay out of their own salaries to make everything tidy,” O’Prey says. “They made sure that no one in the neighborhood went hungry, especially in the winter, and even established the city’s first churches.”

Though times were good, George decided to save for a rainy day. He spent $14,000 on gold coins and excavated the front steps of his house to bury the small fortune. That’s when things got hairy.

Monopolies and Missing Gold

The first monopolies soon started to stake out the brewery scene: Maryland Brewing Company tried to absorb the competition by going after the region’s top 17 breweries. In 1899, Maryland Brewing Company offered George around $3 million for his business, and he decided to sell — much to the disapproval of his sons, Fred and William.

To say George’s sons were upset would be an understatement. The young men relinquished their stock, and Fred even moved away from the “family block.” He specifically went into business to put the monopoly out of business, even though his dad was on the board.

Photo by Flickr/Portable Antiquities Scheme

Thankfully, the father and sons managed to reconcile before George passed away. However, when the family went to excavate the front steps after his death, they recovered a mere $4,000 worth of gold coins.

“What happened to the other $10,000 remains unknown,” O’Prey says. “George’s wife was the executor of the estate, which was pretty rare for the time. She refused to take the stand during the court proceedings, which certainly made her look a bit shady. However, she doled out the inheritance evenly among all three kids, and the judge decided she’d done her job. The missing gold was simply a mystery.”

Historical Craft Beer

For O’Prey and Neff, re-creating an original Bauernschmidt Pilsner was the perfect way to pay homage to the legendary family, and no stone was left unturned in their research.

“Agricultural records became my best friend in trying to uncover the facts. Where was George getting his malts? Where were his grains grown? What kind of barley was available?” O’Prey says.

She pored through the import and export records in old trade magazines, trying to decipher what was or wasn’t selling at the time. O’Prey also had to consider George’s frugal nature, distinguishing which ingredients might have been prohibitively expensive for him.

“Hops are used twice in brewing: They’re boiled in the beginning, and then added again at the end for extra aroma. We knew it was most likely that George used the more expensive German hops in the tail end of the process,” O’Prey says. “It was fascinating to take all of these historical pieces and put them together like a puzzle for the best possible re-creation.”

Photo by Checkerspot

When O’Prey’s sleuthing finally resulted in a complete physical process, she passed the brewing baton to Neff, who tinkered with the blueprint for weeks. Here, Neff’s brilliance was on full display. The result was a super smooth, slightly dry “Hillbilly Gold” pilsner with quite the backstory, one that makes each swig more reverent. The ultimate seal of approval? A thumbs-up from a living descendant of George Bauernschmidt, who happens to be one of the best mead-makers in Maryland. He was overjoyed to see his family’s legacy carried on.

O’Prey and Neff have a few upcoming collaborations. Though they can’t divulge the full details, O’Prey hints that one recipe is from a female brewer in the early 19th century, and another is from after the Cullen-Harrison Act took effect in April 1933 — a few months before the end of national Prohibition — allowing the sale of beers and wines with low alcohol content.

“There’s nothing better for me than seeing people get excited about history,” she says. “Doing so through craft beer that they enjoy? It’s a dream come true.”

Craft Beer Comes Full Circle

According to both Neff and O’Prey, it’s a great time to be a craft beer lover in Charm City — and with so many new taprooms and breweries popping up, it’s an honor to help put in context how the industry has come full circle.

“The climate in post-Prohibition Baltimore wasn’t conducive to the survival of small, local breweries for a number of reasons, and they were almost lost altogether for a few decades,” O’Prey says. “Today, I’d put a Maryland beer over anything in California, Vermont, North Carolina … any state.”

Beyond women reclaiming their place on the front lines, O’Prey is thrilled to note the revival of yet another pre-Prohibition tradition: brewing for the greater good. Maryland brewers are putting their profits toward all sorts of local causes, from saving the Chesapeake Bay, to using oyster shells for their stouts, to supporting local animal shelters.

“There’s an amazing understanding and partnership. Maryland brewers are all in this together,” she says. “If someone has a broken clamp or valve, you can bet another brewery is jumping in to help. It doesn’t matter if you’re new to the industry, male or female — there’s just this connectivity. It’s humbling to be part of that, because they’re all such great people with a vision. Every time I turn around, a Maryland brewer surprises me.”

Hannah Chenoweth is a Baltimore-based writer who enjoys covering health, wellness, and human-interest stories. You can follow her on Twitter @HannahChen2, or visit her website to connect.